Adopting a Zero-Emissions Standard for New Buildings

By Vincent Martinez, Chief Operating Officer, Architecture 2030

Through his over twelve-year tenure at Architecture 2030, Vincent Martinez has developed robust networks focused on private sector commitments, education and training. Vincent has strong connections to private sector leaders in urban real estate through his previous role as the 2030 Districts Network Interim Director from 2013 to 2016, helping co-found the 2030 Districts model that has now been adopted by 20 North American cities. He now sits on the 2030 Districts Network Board of Governors. Vincent also formerly managed the development and dissemination of the AIA+2030 Professional Education Series, which provided design professionals in 27 markets across North America with strategies for reaching zero-net-carbon buildings and has since been developed into an online education series. Vincent currently leads Architecture 2030’s work on urban zero-net-carbon buildings, including the ZERO Code, Achieving Zero framework, and Zero Cities Project with 11 leading US cities. Vincent is the 2018 Chair of the American Institute of Architects’ Energy Leaders Group and is a member of the AIA 2030 Commitment Working Group. He is an honorary member of AIA Seattle and was named an Emerging Leader by the Design Futures Council in 2015.

THE CONTEXT

The UN’s 2017 “Global Status Report” estimates that the world will add 230 billion square meters (2.5 trillion square feet) of buildings by 2060 – the equivalent of adding an entire New York City to the planet every 34 days for the next 40 years.

Over 50% of this new construction will happen in North America, China and India between now and 2030. During the next wave, the majority of new construction will shift to the global south (Latin America, Africa, and India) where there are mostly voluntary building energy codes or no building energy codes at all.

Coupled with the urgency that the IPCC has placed on the decarbonization of our built environment (both existing and new buildings) over the next decade, it is clear that all building sector actions and policies must be evaluated based on their ability to scale and to have a significant immediate impact on greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

Coupled with the urgency that the IPCC has placed on the decarbonization of our built environment (both existing and new buildings) over the next decade, it is clear that all building sector actions and policies must be evaluated based on their ability to scale and to have a significant immediate impact on greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

While there have been worldwide improvements in building sector energy efficiency, as well as growth in renewable energy generating capacity, these have not been nearly enough to offset the increase in emissions from new construction. As a result, building sector CO2 emissions have continued to rise by nearly 1% per year since 2010. To meet the Paris Agreement targets, action is needed today to implement zero-emissions building standards or codes worldwide.

ZERO-EMISSIONS STANDARDS

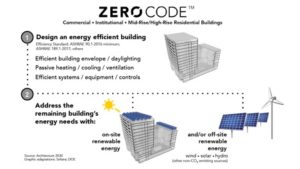

A zero-emissions, or “net-zero”, building standard is one that requires new buildings to be designed and equipped so that all energy use on an annual basis — for heating, cooling, lighting, appliances, vehicle charging, etc. — is highly efficient and comes only from renewable (non-CO2 emitting) energy sources.

Two critical questions that address the scalability and ability of such standards to have significant immediate impact are: 1) how do we define “highly efficient”, and 2) how do we ensure that the energy a building uses comes from “renewable energy sources”? This e-news highlights efforts to answer these questions.

Two critical questions that address the scalability and ability of such standards to have significant immediate impact are: 1) how do we define “highly efficient”, and 2) how do we ensure that the energy a building uses comes from “renewable energy sources”? This e-news highlights efforts to answer these questions.

PRIORITY #1: RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES

This Zero-Emissions Standards Game Changer is inherently linked to and reliant on another strategy: Empower Local Producers and Buyers of Renewable Electricity. While energy efficiency is the primary leverage point of the traditional building energy code structure, zero-emissions buildings cannot be achieved through efficiency alone. It must be complemented with impactful mechanisms for renewable energy generation and procurement to reach zero-emissions standards, especially in jurisdictions with existing highly-efficient codes. Ensuring that the energy needs of new construction are met by renewable energy sources provides the most impactful emissions mitigation strategy for new construction in CNCA cities.

The incorporation of on-site and/or off-site renewable energy requirements has been added to new construction standards across the world. The European Commission’s Technical Standard for Nearly Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB) defines a NZEB as “a very high energy performance building with energy produced by renewable sources on-site or nearby”, and requires new public buildings to reach this standard starting in 2019 and all new buildings to reach this standard starting in 2021. The China Academy of Building Research’s (CABR) recently released Technical Standard for Nearly Zero Energy Buildings also requires on-site and/or off-site renewables.

The World Green Building Council’s Advancing Net Zero Initiative, additionally, provides a framework for defining Zero Net Carbon buildings that recognizes the need for off-site renewables, and to date six Green Building Councils have introduced standards that address on-site and/or off-site renewable energy. More recently the World Green Building Council and C40 launched the Net Zero Carbon Building Commitment, which has 15 businesses, 22 cities and 5 state and regional governments as founding signatories. The commitment follows the EP-100 Technical Criteria for on-site and off-site renewable energy claims and provides a framework for regulating jurisdictions to consider. A new report from C40 also highlights the cities’ planned actions for delivering on the Net Zero Carbon Building Commitment.

Many jurisdictions are also leveraging their building energy codes or local ordinances to lead to, or require, on-site renewable energy generation. For example, on-site solar requirements for new residential construction in the State of California, on-site solar requirements for new non-residential construction in California cities, on-site solar thermal requirements in Sao Paulo and across Europe, and in Durban the eThewini Municipality is exploring land-use planning schemes to require on-site renewables to cover half the building energy needs.

The next option, and most immediately scalable and impactful policy, will be off-site renewable energy procurement requirements, which also address large buildings with limited on-site renewable energy generating capacity (e.g. buildings in dense urban environments). The City of Palo Alto (USA),has a new proposal for their reach code to require on-site and/or off-site renewable energy for new small- to mid-rise non-residential construction, which they have shown to be cost-effective in their climate. The nuances of requiring off-site renewable energy procurement will depend on the local market. An Off-Site ZNE Policy Proposal, ZNE Has Left the Building, submitted by Arup to the California Energy Commission, and Architecture 2030’s ZERO Code, illustrate how this can be implemented.

To create zero-emissions buildings, the focus and urgency must now be on implementing zero-net-carbon building codes and establishing programs and opportunities for off-site renewable energy procurement. This will only accelerate and complement efforts by utilities and regional governments to decarbonize the electricity supply. Lessons learned from the upcoming e-news on Empowering Local Producers and Buyers of Renewable Electricity may be helpful in this regard.

PRIORITY #2: NO NEW ON-SITE EMISSIONS

This Zero-Emissions Standards Game Changer is also linked to the Electrify Buildings’ Heating and Cooling Systems Game Changer. While reaching net zero-emissions is possible now through the purchase of additional renewable energy in order to offset emissions produced by on-site fossil fuels, there is a growing concern that new on-site systems that produce emissions will quickly become a liability and will counteract parallel efforts to electrify existing building heating and cooling systems. Therefore, zero-emissions standards should prohibit, or significantly discourage, on-site fossil fuel use.

Many other cities are working with industry to provide incentives for all-electric buildings, while they work through legislative barriers to its requirement (see CNCA’s Game Changers report). An example is from a recent study performed by the City of Palo Alto (USA), which illustrated that all-electric new construction is cost effective for most building types in their climate, and this is now a central strategy in their upcoming reach code proposal.

PRIORITY #3: INCREASED ENERGY EFFICIENCY

While increased energy efficiency is one of the two central components of Zero-Emissions Building Standards, most advanced jurisdictions already have aggressive energy efficiency requirements for new construction or can adopt the latest model codes (which are highly efficient and include a host of ready-to-use compliance tools). In jurisdictions with high-efficiency codes, the relative emissions reductions from increased energy efficiency in new construction are small, compared to policies that require all new buildings to meet their energy needs from renewable (non-CO2 emitting) sources. Jurisdictions with large amounts of renewable energy in their electricity supply may also see greater emissions reductions from all-electric new construction policies than they would from small incremental efficiency gains.

Jurisdictions that do not have control over their building energy codes will find renewable energy requirements to be one of the only regulatory tools that they can implement to immediately address new construction emissions. For example, the City of Copenhagen doesn’t have control of their building energy codes and is instead working to ensure that Copenhagen is supplied by 100% carbon neutral electricity and heat in 2025, which means their buildings will be zero-net-carbon users.

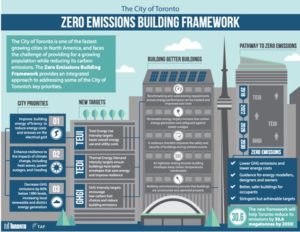

For jurisdictions pursuing advanced energy efficiency through the building energy code structure, innovative strategies are being developed (see infographic on right). Toronto’s proposed Thermal Energy Demand Intensity targets for heating energy and their Greenhouse Gas Intensity targets encourage low-carbon fuel choices and address the two priority areas, all-electric new buildings and the use of renewable energy, discussed above. Vancouver’s building code and rezoning policy already have GHG limits per unit area for most building types and will be updated incrementally so that they will require zero emissions from all new construction by 2030. These types of targets can drive innovation and high levels of efficiency through the performance pathway of the code.

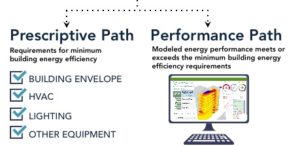

To ensure scalability, zero-net-carbon building energy codes and standards must focus equally on prescriptive and performance code pathways (see figure on left), as the large majority of new buildings around the globe are expected to follow a prescriptive path. Architecture 2030’s ZERO Code provides the framework for linking both the prescriptive and performance path compliance approaches to renewable energy requirements.

To ensure scalability, zero-net-carbon building energy codes and standards must focus equally on prescriptive and performance code pathways (see figure on left), as the large majority of new buildings around the globe are expected to follow a prescriptive path. Architecture 2030’s ZERO Code provides the framework for linking both the prescriptive and performance path compliance approaches to renewable energy requirements.

CONCLUSION

The urgency of the climate crises and the scale of expected global new construction makes highly efficient building energy code adoption, coupled with on-site and off-site renewable energy requirements, the most critical policy for all new buildings in CNCA cities. Renewable energy requirements can achieve the emissions reductions required for leading cities to reach a zero-net-carbon building sector, and, with building energy codes, are a critically missing policy piece for the rest of the developing world.

It is also worth stressing that in order to truly decarbonize the built environment, we must eliminate fossil fuel GHG emissions from both building operations and the embodied carbon of building materials and construction. To address this urgency, new policies, above and beyond government procurement, must be developed and include prescriptive and performance-based standards and requirements. Stay tuned for more on innovations in this important topic in a future e-news.