Glasgow’s Climate Action Story

By Gavin Slater, Head of Sustainability,

Neighbourhoods & Sustainability, Glasgow City Council

The City of Glasgow has experienced constant change and evolution. In 1765, James Watt, while walking on Glasgow Green, conceived of the separate condenser to the steam engine and, thus, set about an acceleration of the evolution of the industrial age and inadvertently enabled the acceleration of climate change. In the years that followed, Glasgow became an industrial powerhouse.

The ripples from that one moment in time here in Glasgow lapped the shores of the entire world, changing it just as much as it transformed us. Since then we have generated new ways of urban living, but with them has come the generation of the greenhouse gases that have come back to haunt our legacy. Now we look to atone for the sins of the carbon age and to open a new chapter in our city’s journey to a cleaner, greener future. Indeed, now we look once more to draw upon that native Glaswegian spirit of innovation and entrepreneurialism to create a new economy and society, one being forged in the crucible of the renewables revolution.

The Need for a Just Transition

Social justice and the just transition are at the heart of this approach. The Council manages the most extensive programme of domestic energy efficiency support in the country in order to tackle fuel poverty and helps to provide affordable warmth for its most vulnerable citizens. Further plans by the City Government for an energy services company and more low carbon heating systems will contribute to this important agenda.

Engagement with communities in the age of climate change is also particularly significant and the Council has helped to lead a pilot project called Weathering Change in the north of the city to grow local action in partnership with communities on climate issues. The city is also fortunate to have a unique global resource at Glasgow Caledonian University, called the Centre for Climate Justice, which works to support what Mary Robinson calls ‘a just transition to a safer world’. It reflects the city’s outward-looking and internationalist perspective on this issue, as well as acknowledging the post-colonial legacy of Glasgow’s role.

The Roadmap: Assessing and Goal-Setting

Glasgow has since set about reinventing itself as an important member of the world’s leading cities in addressing climate change. In 2010, the city established the Sustainable Glasgow partnership, an innovative partnership between the public, academic, and private sector, tasked with supporting the city in achieving a reduction in its carbon emissions of 30% by 2020, based on a 2006 baseline. In 2010 this was visionary, and a step ahead of the 20% target for 2020 set by the EU and, by 2017 (data are always reported 2 years in arrears), Glasgow had successfully reduced reduced CO2 emissions by 37%, meeting and exceeding our target years in advance.

During the years that have passed since 2010, Glasgow has been very active in establishing various different measures with which we can tackle climate change, both through adaptation and mitigation.

In 2014, the city established its Energy & Carbon Masterplan (ECMP) which examined energy use in the city in great detail and utilised spacial mapping of consumption aligned to social metrics, such as poverty, to devise 33 actions that, if implemented, would reduce Glasgow’s CO2 emissions by 30% by 2020 on a 2006 baseline.

As of 2017, the city had successfully reduced emissions by 37%. The ECMP pioneered a number of approaches to energy planning, one of which was the development of heat mapping to visualise how much heat was being consumed and where. Initially this was done through the use of data bought from credit card companies and building surveyors.

We have come a long way since then: these data are now collated nationally, providing a much better visual of heat consumption and allowing much better planning of new heating systems that enable less expensive, and less carbon intensive, heat production, distribution and consumption for those most in need.

Furthermore, the council, working with internal and external partners, is assessing the risks of projected climate change to the city and the city council. Specifically, they are looking at the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment report for Scotland, 15 key consequences of climate change for Scotland, and the Climate Change Risk and Opportunity Assessment for the city region.

Flourishing in the Face of Climate Change

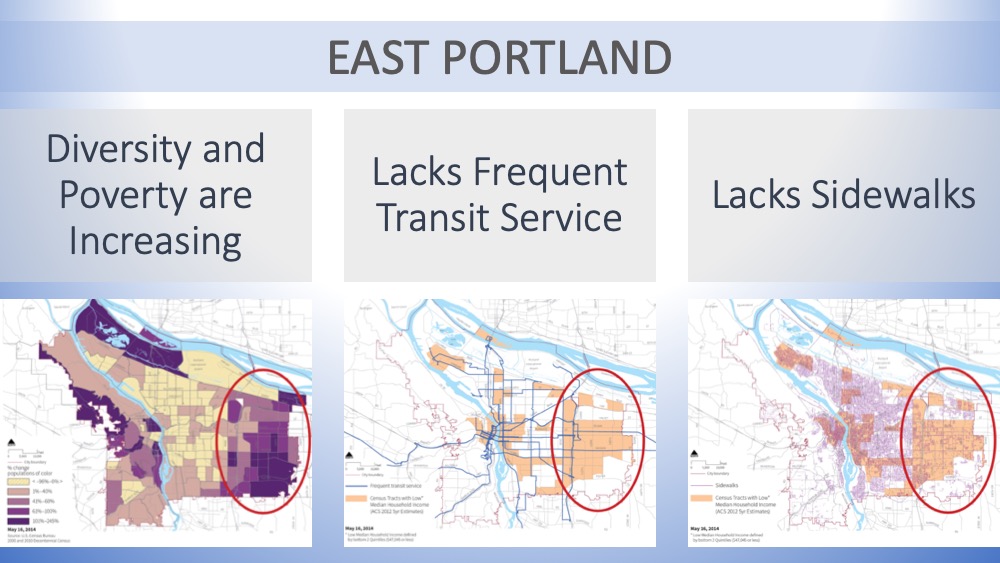

A climate adaptation action plan is being created that aims to address climate resilience in the city, ensuring that the most vulnerable in our city aren’t disproportionately impacted by impacts of a changing climate, such as flooding, overheating, food unavailability/high costs, or access to good quality housing and transport. The strategy aims to help Glasgow’s people, economy, natural environment and key infrastructure to flourish in the face of a changing climate.

The City Council is also one of the founding members of the Climate Ready Clyde Partnership managed by SNIFFER. Partners include Clydeplan, Glasgow & Clyde Valley Green Network, Local Authorities in the Clyde Valley, NHS GG&C, Transport Scotland, SEPA and Scottish Power Energy Networks. The council plays a role alongside other partners in developing a climate adaptation strategy for the city region.

The city has issues with fuel poverty, in which people spend more than 10% of their income on energy bills. This is often due to the perfect storm of low income households living in poorly insulated homes with inefficient heating systems. This is unacceptable and the council has been working hard with stakeholders to replicate the innovative district heating systems found all across Europe, particularly in Scandinavia.

Glasgow is now home to a number of innovative district heating systems that utilise gas CHP and air source heat pumps to deliver low carbon, low cost heating to help reduce the carbon impact of heating and to alleviate those in fuel poverty by providing affordable warmth, ensuring those in most need get the help they require.

Future district heating systems will likely be mostly heat pump driven, as electricity in Scotland has a very low carbon coefficient and heat pumps have such a high coefficient of performance. The developing Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategy will identify where new district heating schemes will be placed to continue to minimise the carbon cost of heating in Glasgow.

In addition to district heating, the city has deployed renewable energy in a big way. Social housing in Glasgow is owned and operated by Resident Social Landlords or Housing Associations. Many of these have deployed solar PV to supply low cost and low carbon energy to their tenants and to reduce their carbon footprint. Again, the purpose is to provide alleviation of fuel poverty, a key principle of Glasgow City Council, as it transitions towards a sustainable future in a just way.

As well as solar PV, Glasgow City Council, in partnership with Scottish and Southern Energy, installed a 3MW wind turbine in the city, which is a major feat in a dense city situated close to an international airport. Revenue generated by this turbine is shared with a local community trust to be used to develop more local renewable projects and community benefit projects and ensure that the benefits are retained in the local area, an area which scores high on many indices of deprivation. This is another way in which the city is trying to ensure a just transition to a low carbon future.

Other projects are being developed with community groups that follow a similar model, with the council providing buildings that community groups can use to install renewables and benefit from energy sales.

Addressing Future Climate Risks: Floods and Food Systems

Another way in which climate change is affecting Glasgow specifically is in local flooding. Glasgow City Council is a lead partner in the Metropolitan Glasgow Strategic Drainage Partnership (MGSDP – www.mgsdp.org), a non-statutory, collaborative, partnership and NPF3 National Development, with the aim to Sustainably Drain Glasgow.

Collectively, the partners have delivered over £500M of projects to date, to reduce flood risk, improve water quality and enable sustainable economic development in the Glasgow region.

Working with partners, key projects that GCC has led successful delivery of include the White Cart Flooding Project, the Camlachie Burn Overflow, Toryglen Regional SuDS Pond, Cardowan Surface Water Management Plan and Glasgow’s Smart Canal.

With climate change increasing flood risks and impacts, the partnership continues to deliver projects, with GCC leading the design and construction of a number of surface water management projects across Glasgow, many with Glasgow City Region City Deal funding, that will reduce flood risk through the delivery of sustainable blue-green infrastructure.

GCC also has the role of Lead Local Authority for the Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District, and is working closely with SEPA to develop the 2nd Flood Risk Management Strategies for public consultation at the end of this year (it may be pushed back six months due to Covid-19), with the aim of identifying further projects to increase resilience to existing and future flood risk.

The future of food is another pressing issue for the citizens of Glasgow. More and more people are becoming acutely aware of the impact of food production and consumption on the planet and are very concerned about how the city can address this in a way that is just and equitable.

Glasgow recently held an Inquiry and a Food Summit involving over 100 community and other food groups, and international representatives from the Milan Urban Food Pact Policy Partnership of which both cities are members. A co-design process has followed and a strategy and City Food Plan is in development with the umbrella body Glasgow Community Food Network.

Glasgow City Food Plan is an ambitious cross-sector piece of work that aims to transform Glasgow’s food system to one that is integrated, holistic, healthy, fair and sustainable. This draft strategy – called “Let’s Grow Together 2020-25” – includes reducing carbon emissions. The Circular Economy features quite strongly throughout the plan and in the community and enterprise elements especially. Addressing poverty, particularly children’s poverty, is a key part of this, as exemplified by the Council’s Children’s Holiday Food programme.

The Council is working with GCFN to develop a partnership between six community food organisations around the city which will enable communities to participate in and lead on aspects of the upcoming City Food Plan.

In summary, all of these strategies and policies are designed to transition the City of Glasgow from its carbon based heavy industry to a sustainable, carbon neutral future, in a way that is just and equitable for all of the citizens of Glasgow.

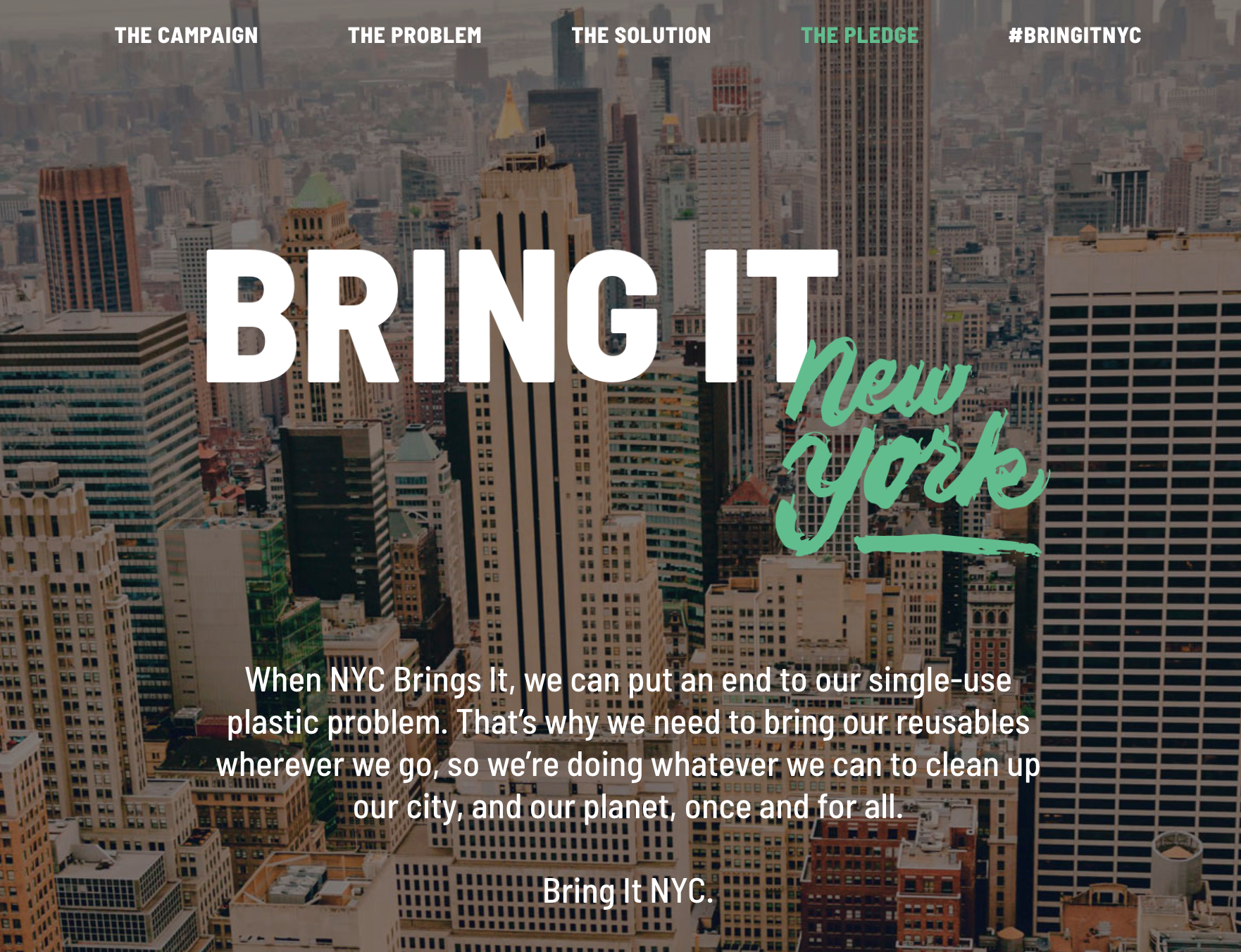

It’s not uncommon to find CNCA member websites advocating for myriad actions and initiatives, because the work is massive in scope. Whether it’s big building retrofits, green energy installs, public transit improvements, waste management, bike lane build-outs, or household weatherization, there’s so much that needs to be pursued now. But is there a way to deliver this to users that doesn’t cause choice overload? And is there a way to deliver it, as

It’s not uncommon to find CNCA member websites advocating for myriad actions and initiatives, because the work is massive in scope. Whether it’s big building retrofits, green energy installs, public transit improvements, waste management, bike lane build-outs, or household weatherization, there’s so much that needs to be pursued now. But is there a way to deliver this to users that doesn’t cause choice overload? And is there a way to deliver it, as

There’s plenty of research in the social science field on how fatigue makes for bad decision-making. Considering this when we reach out to the community to build public and political will, are we cognizant of when and where they might be fatigued (and thus less equipped to support our climate initiatives)? And when we’re hosting events, are we bringing food so that we’re enabling the community of decision-makers to be well-equipped to get on board a sustainability decision?

There’s plenty of research in the social science field on how fatigue makes for bad decision-making. Considering this when we reach out to the community to build public and political will, are we cognizant of when and where they might be fatigued (and thus less equipped to support our climate initiatives)? And when we’re hosting events, are we bringing food so that we’re enabling the community of decision-makers to be well-equipped to get on board a sustainability decision?

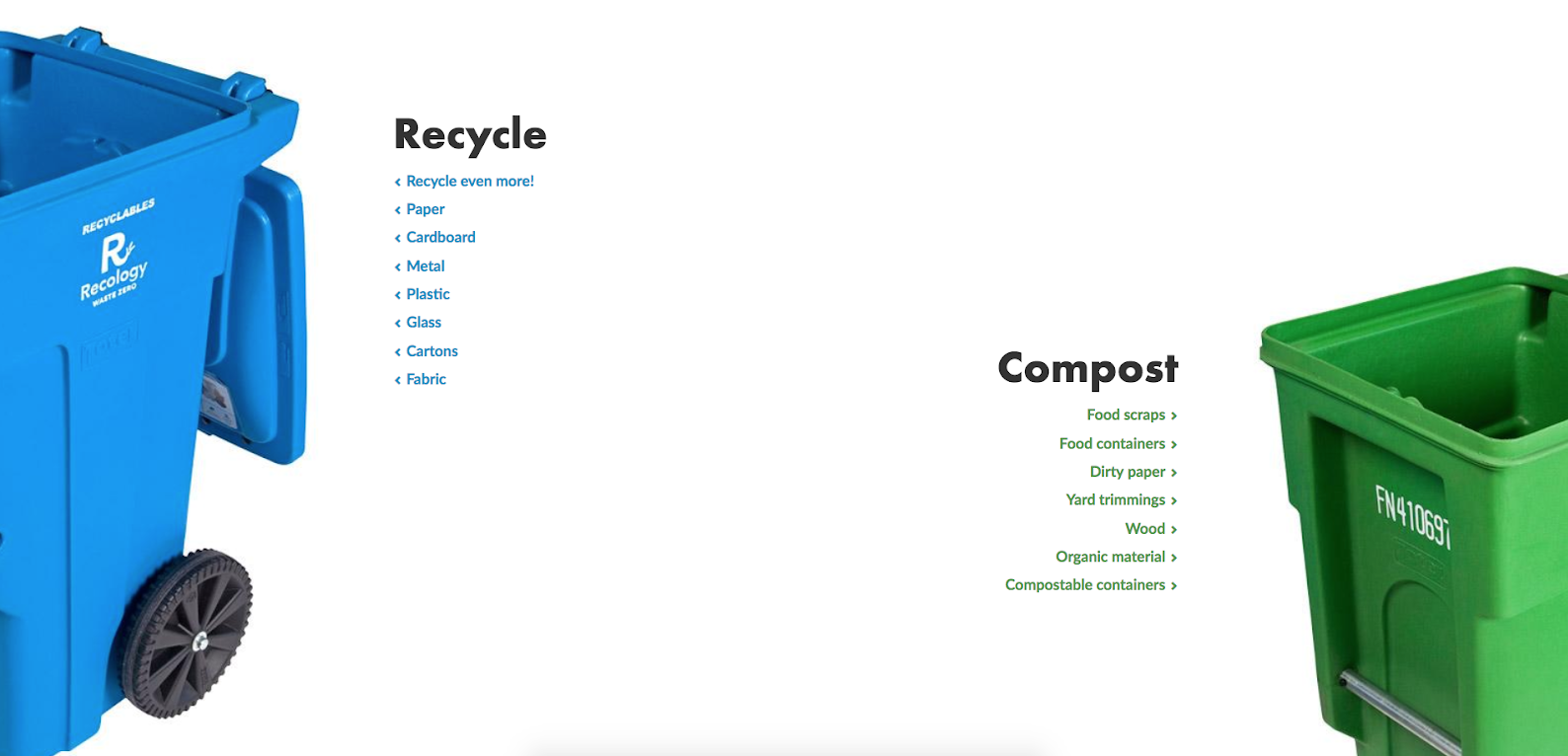

How do we make green choices easy for our community? If we want them to ride the bus more, bike more, eat more plant-based foods, waste less, weatherize more, and buy heat pumps and solar power, how do we make it hassle-free or close to hassle-free?

How do we make green choices easy for our community? If we want them to ride the bus more, bike more, eat more plant-based foods, waste less, weatherize more, and buy heat pumps and solar power, how do we make it hassle-free or close to hassle-free?

Since not everyone considers themselves an environmentalist, how do we tap into and resonate with other identities that might be attracted to our climate policies? When we think of the myriad ways in which our communities self-identify, what are the principles that matter to them? Parents, for example, would have, as part of their identity as guardians, a desire to keep their children safe from harm and to provide for their household. In that one sentence, we’ve covered health, security and economics. Are we mindful of this when messaging and mobilizing our climate initiatives? And in the words of

Since not everyone considers themselves an environmentalist, how do we tap into and resonate with other identities that might be attracted to our climate policies? When we think of the myriad ways in which our communities self-identify, what are the principles that matter to them? Parents, for example, would have, as part of their identity as guardians, a desire to keep their children safe from harm and to provide for their household. In that one sentence, we’ve covered health, security and economics. Are we mindful of this when messaging and mobilizing our climate initiatives? And in the words of

When our communities don’t immediately respond to our climate requests it’s not because they’re not interested. Perhaps they only heard it once from us, perhaps they never heard it at all, or perhaps other priorities took their attention at the time. Mindful of our own limited attention spans, and being cognizant of all that’s taking priority in residents’ lives, how do we make it easy for them to hear from us by repeating and reiterating our work through every possible channel that might reach them? Are we simultaneously using radio, television, billboards, community newspapers and newsletters, local associations and advocacy organizations, religious halls, phone and email, text and other ways to communicate with the public?

When our communities don’t immediately respond to our climate requests it’s not because they’re not interested. Perhaps they only heard it once from us, perhaps they never heard it at all, or perhaps other priorities took their attention at the time. Mindful of our own limited attention spans, and being cognizant of all that’s taking priority in residents’ lives, how do we make it easy for them to hear from us by repeating and reiterating our work through every possible channel that might reach them? Are we simultaneously using radio, television, billboards, community newspapers and newsletters, local associations and advocacy organizations, religious halls, phone and email, text and other ways to communicate with the public?

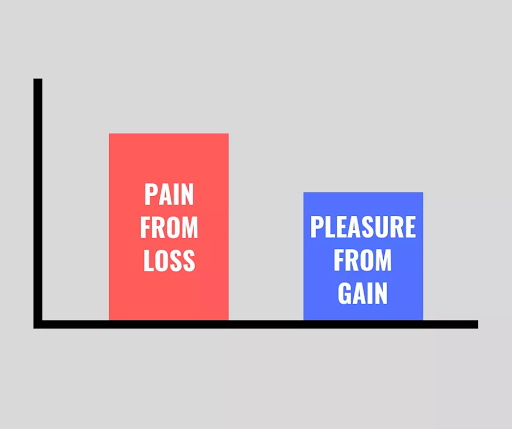

People have an intrinsic disdain for loss. We get attached. And we hold onto that attachment – be it emotional, relational, physical or spiritual. So, how do we communicate our climate work in such a way that it’s mindful of the public’s proclivity for avoiding loss? When we think about what people care about – quality of life, standard of living, ego, money, health, and physical security – are we articulating our work in such a way that is mindful of what they don’t want to lose?

People have an intrinsic disdain for loss. We get attached. And we hold onto that attachment – be it emotional, relational, physical or spiritual. So, how do we communicate our climate work in such a way that it’s mindful of the public’s proclivity for avoiding loss? When we think about what people care about – quality of life, standard of living, ego, money, health, and physical security – are we articulating our work in such a way that is mindful of what they don’t want to lose?

There is a bias towards information that’s presented first, versus information that’s less visible. How does that bias impact how we message climate, then? Is it presented in a highly visible way on our websites and do we have social media channels specifically devoted to our climate and sustainability work (to send a message to the public that this is a priority)? Are our mayors and city staff leading with the climate message or are they placing it last on a list?

There is a bias towards information that’s presented first, versus information that’s less visible. How does that bias impact how we message climate, then? Is it presented in a highly visible way on our websites and do we have social media channels specifically devoted to our climate and sustainability work (to send a message to the public that this is a priority)? Are our mayors and city staff leading with the climate message or are they placing it last on a list?

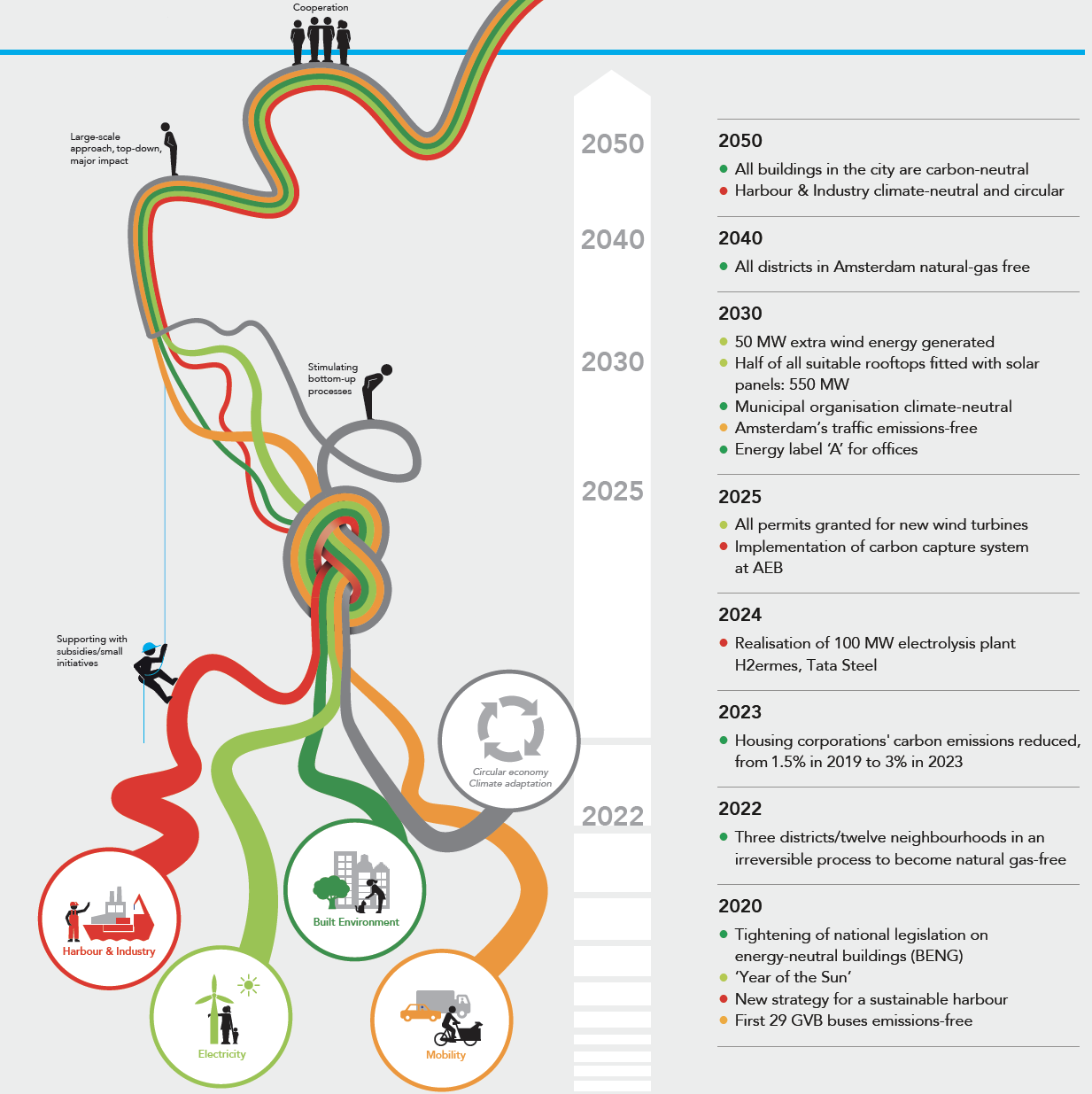

Everyone procrastinates on something at some point in their day/week/month, which is why any far off “2050” framing for our climate initiatives is potentially problematic. Even 2040 or 2030 seems far off. People will wait until the last minute to do whatever it is we’re asking them to do. It’s why it’s problematic for us to talk about future impacts; it merely reinforces the proclivity to procrastinate. We need to talk about impacts that are happening here and now. We need to offer easy, bite-sized steps that anyone can take now. And we need public-friendly short-term climate goals and deadlines to balance our plethora of long-term climate goals.

Everyone procrastinates on something at some point in their day/week/month, which is why any far off “2050” framing for our climate initiatives is potentially problematic. Even 2040 or 2030 seems far off. People will wait until the last minute to do whatever it is we’re asking them to do. It’s why it’s problematic for us to talk about future impacts; it merely reinforces the proclivity to procrastinate. We need to talk about impacts that are happening here and now. We need to offer easy, bite-sized steps that anyone can take now. And we need public-friendly short-term climate goals and deadlines to balance our plethora of long-term climate goals.

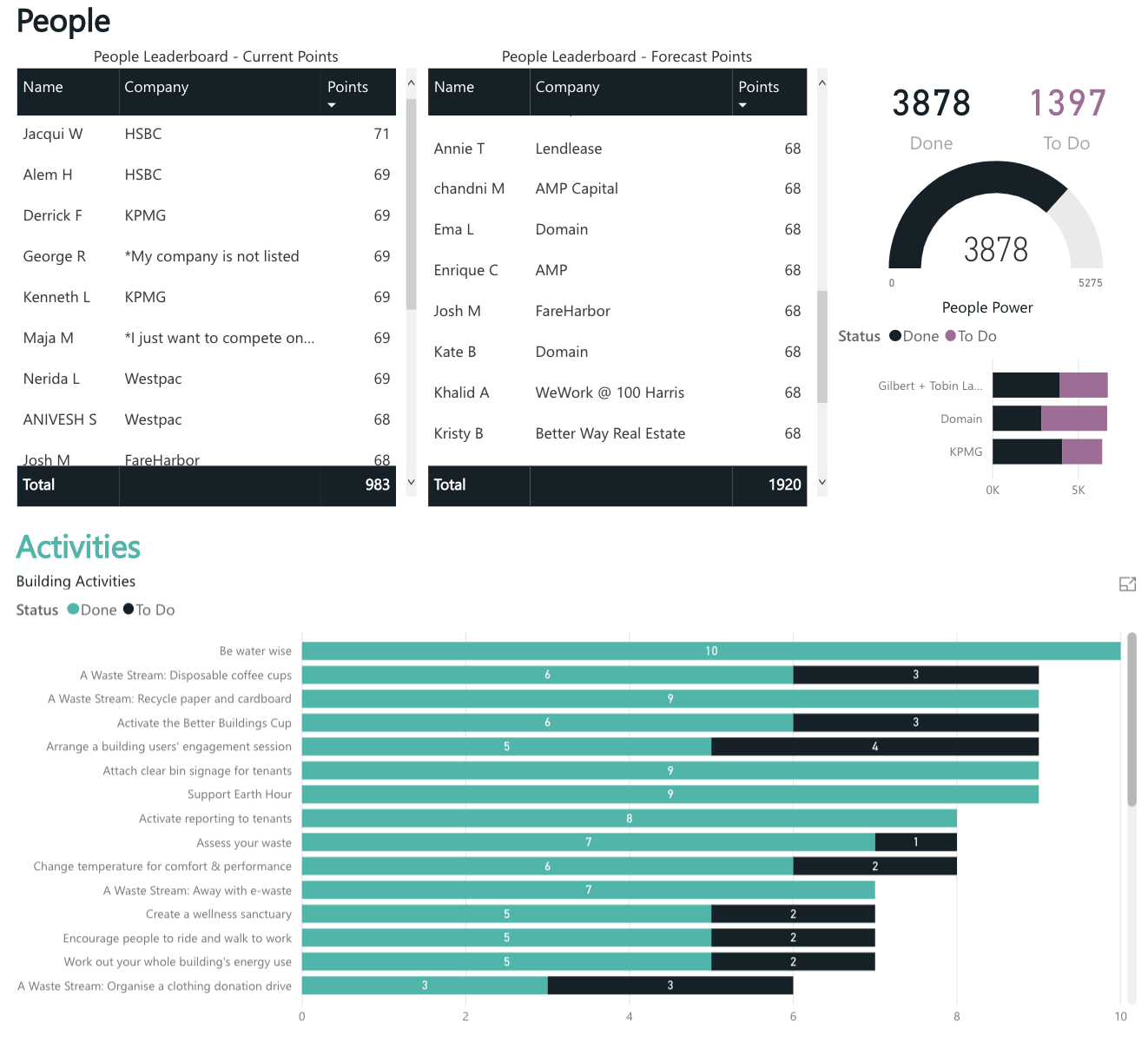

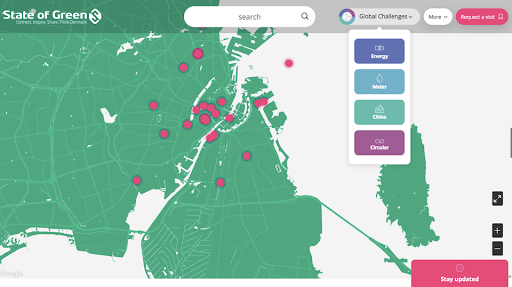

We all know the power of social norming. Approval matters. We all know the study that shows that if your neighbor has solar panels, you’re more likely to get solar panels. And if your neighbor is saving money on their utility bill, due to some energy efficiency measures, you’re more likely to pursue the same or better savings by taking similar action. Given this, how can we use our city communication vehicles to show that a movement is happening in our cities and that our public and private sectors are changing the game? How are we reflecting back community actions so that residents and building owners see their peers taking action across the city and are motivated to do what others are doing?

We all know the power of social norming. Approval matters. We all know the study that shows that if your neighbor has solar panels, you’re more likely to get solar panels. And if your neighbor is saving money on their utility bill, due to some energy efficiency measures, you’re more likely to pursue the same or better savings by taking similar action. Given this, how can we use our city communication vehicles to show that a movement is happening in our cities and that our public and private sectors are changing the game? How are we reflecting back community actions so that residents and building owners see their peers taking action across the city and are motivated to do what others are doing?

Default settings are powerful. We like routine. If a status quo has been established, we’re less likely, in general, to deviate from that. So, how does this principle impact our city-based, climate-focused behavior change communications?

Default settings are powerful. We like routine. If a status quo has been established, we’re less likely, in general, to deviate from that. So, how does this principle impact our city-based, climate-focused behavior change communications?

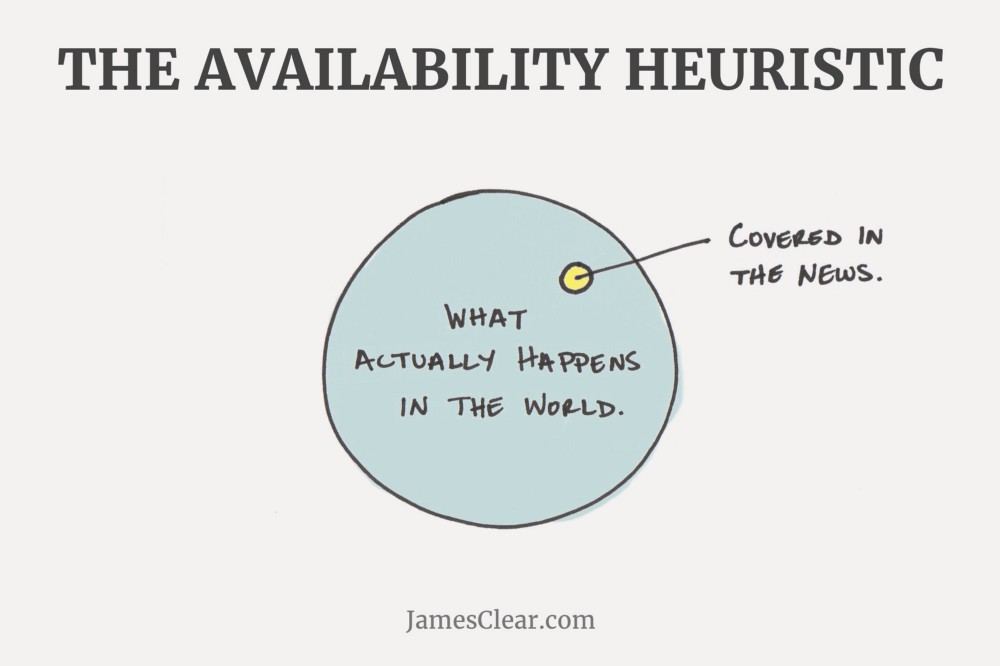

Our publics may think they’ve never experienced a climate impact before, or if they have there’s only been a few events, not many. This is due, in part, to the fact that the press and often policymakers aren’t contextualizing extreme weather events within a global warming reality. The availability of our climate memory, and how easily things come to mind where the climate dots are connected, is limited. This is a problem because, as

Our publics may think they’ve never experienced a climate impact before, or if they have there’s only been a few events, not many. This is due, in part, to the fact that the press and often policymakers aren’t contextualizing extreme weather events within a global warming reality. The availability of our climate memory, and how easily things come to mind where the climate dots are connected, is limited. This is a problem because, as

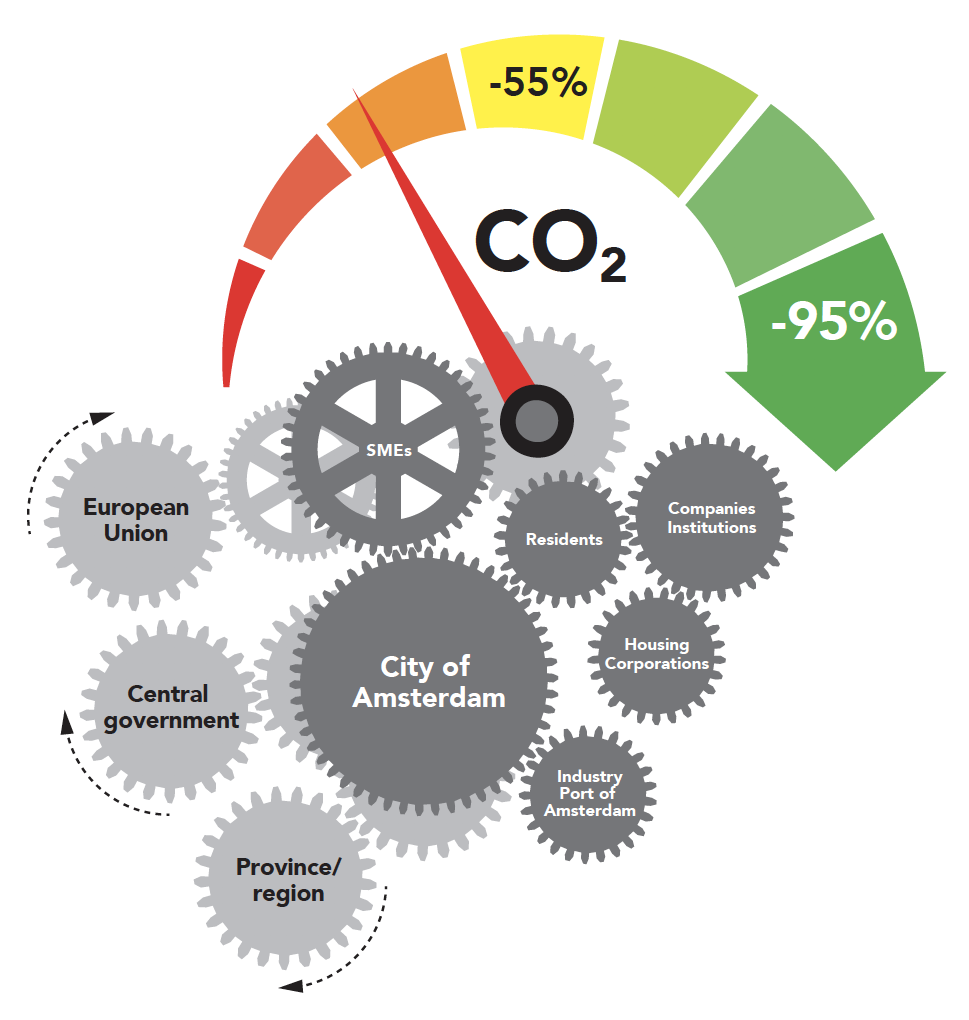

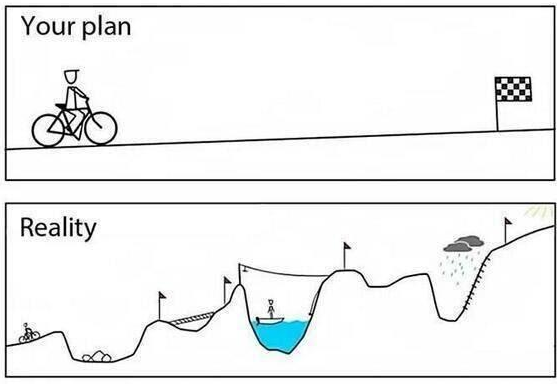

Humans rarely account for and allocate sufficient time for a given task. We’re overly optimistic about how much time it will take to accomplish a specific task. This has huge implications for any of our sustainability targets and timelines for 2030, 2040 and 2050. And why it’s essential to be very clear about how much time these tasks will take. Reorient the deadlines so that it’s an easier estimable planning period for the public (since we aren’t often planning other tasks in 20 or 30 year timeframes). Admittedly, since city-scaled game-changing will take time, we want to be both clear about the necessary planning and positive about our ability to accomplish the task so that the public isn’t overwhelmed by the amount of time needed.

Humans rarely account for and allocate sufficient time for a given task. We’re overly optimistic about how much time it will take to accomplish a specific task. This has huge implications for any of our sustainability targets and timelines for 2030, 2040 and 2050. And why it’s essential to be very clear about how much time these tasks will take. Reorient the deadlines so that it’s an easier estimable planning period for the public (since we aren’t often planning other tasks in 20 or 30 year timeframes). Admittedly, since city-scaled game-changing will take time, we want to be both clear about the necessary planning and positive about our ability to accomplish the task so that the public isn’t overwhelmed by the amount of time needed.