By Alisa Kane, Climate Action Manager, City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability

Portland, Oregon, a city of nearly 650,000 people in the Northwest corner of the United States, has been working to address climate-related issues for over 25 years. As the first U.S. city to adopt a strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in 1993, Portland’s legacy of climate-friendly policies and programs targeting transportation, energy, land use, natural resources and solid waste have contributed to Portland’s steady decrease in carbon emissions. As of 2017, Portland’s per-capita emissions were 38% below 1990 levels.

While Portland is often recognized as a leader in the U.S. on climate action, it doesn’t tell the full story. Portland is the whitest major city in the U.S., with white residents making up 77% of the population. However, white Portlanders are generally not the people already experiencing the harmful effects of climate change. Rather, people of color, low-income residents and Native Americans living in Portland are on the frontlines of climate change. These are the same frontline communities that have largely been denied the benefits that have historically flowed from years of investments in climate-friendly programs, policies and infrastructure and are facing disproportionate climate impacts that take a real toll on their families and communities.

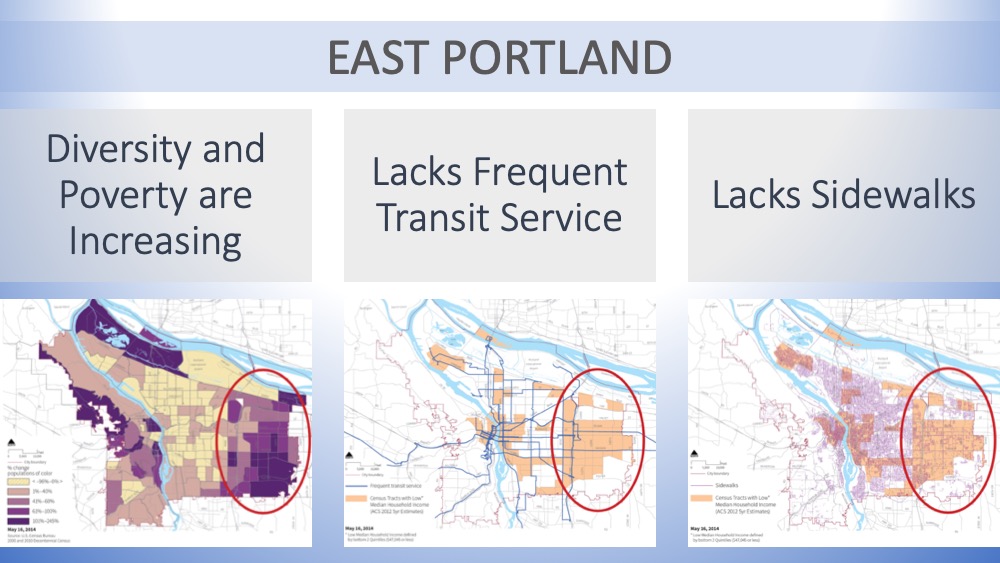

Decades of institutional racism and gentrification have pushed Black, Asian and Latino communities from the central city to outer neighborhoods. Punctuated by freeways, a deficit of trees and parks, and inequitable investments in infrastructure, these areas are also farther from job centers leading to longer commute times and distances, and increased transportation costs. As a result, frontline communities disproportionately experience the negative health effects of dangerously poor air quality, urban heat islands and unsafe transportation connections. This is the Portland climate story that has not been told and is why the update to Portland’s Climate Action Plan will center on prioritizing high-impact carbon emission reduction strategies that are focused on improving the health, prosperity and resilience of Portland’s frontline communities.

Asking Different Questions

In the coming months Portland will begin hosting collaborative conversations to draft new actions for an updated climate action plan. Through one-on-one conversations, workshops, forums, events and technology, local government staff will engage climate justice leaders, industry groups, environmental organizations and community-based organizations to develop actions that both reduce carbon emissions and create community benefits for those who have been left behind. The goal of this engagement is to uncover new ways of approaching climate action planning.

Here’s an example of how we’re rethinking climate action planning in Portland: Transportation accounts for 42% of Portland’s carbon emissions. In prior climate action plans, the focus has been on increasing walking, biking and mass transit use. Billions of dollars of investment in transit and transit-oriented-development, and bike and pedestrian infrastructure, helped keep downward pressure on emissions. But in recent years, the trend has reversed and is ticking upwards with year-over-year increases resulting in a 14% increase in transportation emissions from their lowest levels in 2012. Portland’s traditional climate planning approach to this problem would be to set even more aggressive targets for increasing bus ridership to reduce vehicle miles traveled, congestion and air pollution.

But does this approach account for the needs and experiences of frontline communities? Before we make increasing bus ridership a signature goal of our next climate plan, we need to ask more questions. Using John Powell’s Targeted Universalism concept, Portland is seeking to move beyond traditional one-size-fits-all approaches which tend to exacerbate existing inequities. We’re looking to develop climate actions that simultaneously aim for a universal goal (e.g., increasing transit ridership), while also addressing disparities in opportunities among frontline communities. So, instead of asking ourselves questions like “how do we get more people on the bus?” we should instead be asking more probing questions like, “who can’t ride the bus safely, and why?”

We’ve known that people using buses over cars is better for the climate, even more so if those buses are powered by clean-fuels like electricity, and if frequent routes serve the places where people live, work and play. Equally important is that there is a connected network of sidewalks, crosswalks and accessibility features so that people can arrive to the bus stop safely. Like most other CNCA cities, Portland typically designs our climate action plans – and measures our success – around these well-defined physical elements of a world-class transportation system. But that doesn’t tell the full story, and we run the risk of continuing to advance solutions that, in the end, won’t get us to our ultimate carbon goals.

A recent report by Portland’s transportation division, “Walking While Black,” found that Black pedestrians are more likely to be stopped by police while walking, and they experience 32% longer wait times at crosswalks than white pedestrians before drivers yield to them. In addition, almost half of all traffic fatalities in Portland are pedestrians, and unsafe crossings and the lack of sidewalks in many frontline communities put people, especially youth and people with disabilities, at higher risk of injuries or even death by automobiles. Finally, we need to acknowledge that there are real dangers to riding transit. Misogyny, homophobia, Islamophobia and other forms of oppression don’t disappear once the door of the bus opens. From verbal harassment to physical attacks, Portland’s transit system is far from safe for everyone.

What Can Local Governments Do?

Without addressing these underlying systematic issues, we’ll never get enough people riding the bus to greatly decrease our carbon emissions. Doing what we’ve always done (e.g., more transit routes, electric buses) but just doing those things harder, faster or with better messaging isn’t going to work. Fortunately, local governments are uniquely positioned to employ new approaches to address the intertwined challenges of both climate change and social injustice. In Portland, the local government significantly influences and/or runs the transit system, manages many transportation infrastructure projects, invests in affordable housing and homelessness services, and oversees the police bureau. This may mean that Portland’s next climate plan will include actions that address racial profiling by police, or penalize car drivers that don’t yield the right-of-way to pedestrians in frontline communities.

Simply by asking different questions (e.g., “who can’t ride the bus safely and why?” versus “how do we get more people riding the bus?”), Portland’s new approach to climate action planning is poised to redefine what successful climate action looks like. To fully address the urgency of preparing for and mitigating the disastrous impacts of climate change, Portland will need to strategically focus on actions that significantly reduce carbon emissions, create just and equitable solutions, and offer tangible benefits to the frontline communities most impacted by climate change.